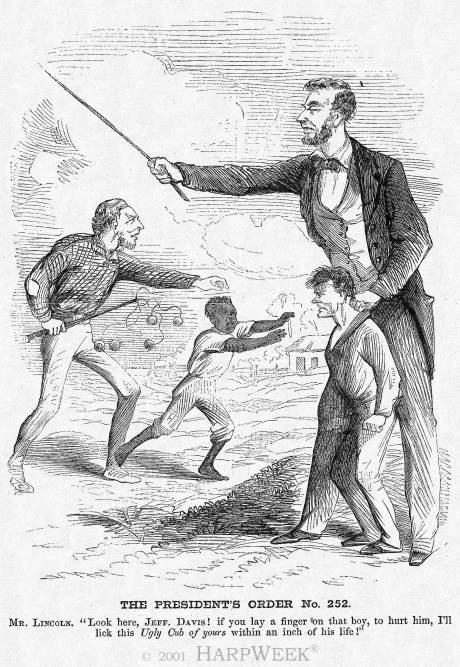

On August 15, 1863, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon about the treatment of black prisoners of war during the Civil War.

The President's Order No. 252

This cartoon depicts President Abraham Lincoln's response to the Confederate practice of treating captured black Union servicemen more harshly than their white comrades, even to the extent of enslaving them. The president's policy--Order No. 252--was essentially to respond in kind to the maltreatment. That sentiment is expressed in this cartoon where Lincoln threatens to beat the Confederate sailor he holds by the collar if Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president, harms the black boy he is chasing with a cat-o-nine-tails. The unevenness of the fight, though, is conveyed by embodying Lincoln's personal prestige and the Union's military force in the Union president's gigantic size.

Mr. Lincoln. "Look here, Jeff. Davis! if you lay a finger on that boy, to hurt him, I'll lick the Ugly Cub of yours within an inch of his life!

Mr. Lincoln. "Look here, Jeff. Davis! if you lay a finger on that boy, to hurt him, I'll lick the Ugly Cub of yours within an inch of his life!

Artist: unknown

In July 1862, Congress authorized the president to use black troops, but the policy was not pursued until after the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. The two issues were related in the minds of many Americans. Lincoln hoped to undermine Confederate moral by proclaiming the freedom of slaves in Confederate territory and by using black men in the Union military. Black servicemen viewed Union military service, especially following the Emancipation Proclamation, as a chance to participate in an army of liberation. On the other side, Confederates feared that the two Union policies could encourage bloody slave revolts and retaliatory actions by aggrieved blacks.

In January 1863, Confederate President Davis initially vowed to turn Union officers over to state governments to be punished (i.e., executed) as criminals inciting slave rebellions. He backed away from that policy, but the Confederates executed some black soldiers and their white officers. On May 30, 1863, the Confederate Congress stipulated that captured white officers of black troops be tried and punished by military courts, while the former slaves be tried in state courts. However, a number of black Union soldiers were summarily shot while allegedly trying to escape.

On July 30, 1863, President Lincoln issued General Order No. 252:

"It is the duty of every Government to give protection to its citizens, of whatever class, color or condition, and especially to those who are duly organized as soldiers in the public service. The law of nations, and the usages and customs of war, as carried on by civilized powers, permit no distinction as to color in the treatment of prisoners of war as public enemies. To sell or enslave any captured person on account of his color, and for no offense against the laws of war, is a relapse into barbarism, and a crime against the civilization of the age."

"The Government of the United States will give the same protection to all its soldiers, and if the enemy shall sell or enslave any one because of his color, the offense shall be punished by retaliation upon the enemy's prisoners in our possession. It is therefore ordered, that for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the law, a Rebel soldier shall be executed, and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a Rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works, and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and receive the treatment due to a prisoner of war."

Lincoln's retaliatory order was difficult to put into practice. After a massacre of black soldiers at Fort Pillow (April 12, 1864), the president and his military advisors decided to punish the Confederates directly responsible, should they be captured, rather than to randomly execute a corresponding number of Confederate prisoners of war. Field commanders near Richmond, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina carried out the Union’s only official retaliations. When Confederates forced captured black soldiers to build fortifications in the line of fire, the Union officers made an equal number of Confederate prisoners perform similar work. Thereafter, the Confederates stopped the practice.

The Confederacy’s refusal to acknowledge captured black servicemen as legitimate prisoners of war halted prisoner-of-war exchanges in the summer of 1863. By the end of the year, the Confederacy was willing to discuss returning black soldiers who upon enlistment had been legally free as the Confederacy defined it (i.e., not under the Emancipation Proclamation). That position was not sufficient for top Union officials--President Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and General Ulysses S. Grant--who remained steadfastly committed to ensuring the equal treatment of Union prisoners of war. Davis and Confederate officials finally relented in January 1865, agreeing to exchange all prisoners. A few thousand prisoners of war, including freed slaves, were exchanged by the Confederacy and Union until the end of the war in April.

For more information on blacks and the Civil War, visit HarpWeek’s Black American History Website:[http://blackhistory.harpweek.com/]

Robert C. Kennedy

Mr. Lincoln. "Look here, Jeff. Davis! if you lay a finger on that boy, to hurt him, I'll lick the Ugly Cub of yours within an inch of his life!

Mr. Lincoln. "Look here, Jeff. Davis! if you lay a finger on that boy, to hurt him, I'll lick the Ugly Cub of yours within an inch of his life!